FOLLOWING THE EXAMPLE OF PRINCES AND BISHOPS

Secular and spiritual rulers proudly displayed their "Cabinets of Curiosities", which included paintings and sculptures, but also natural objects such as minerals, shells, stuffed animals and dried exotic plants. Later these collections often provided the basis for museums of art or natural history.

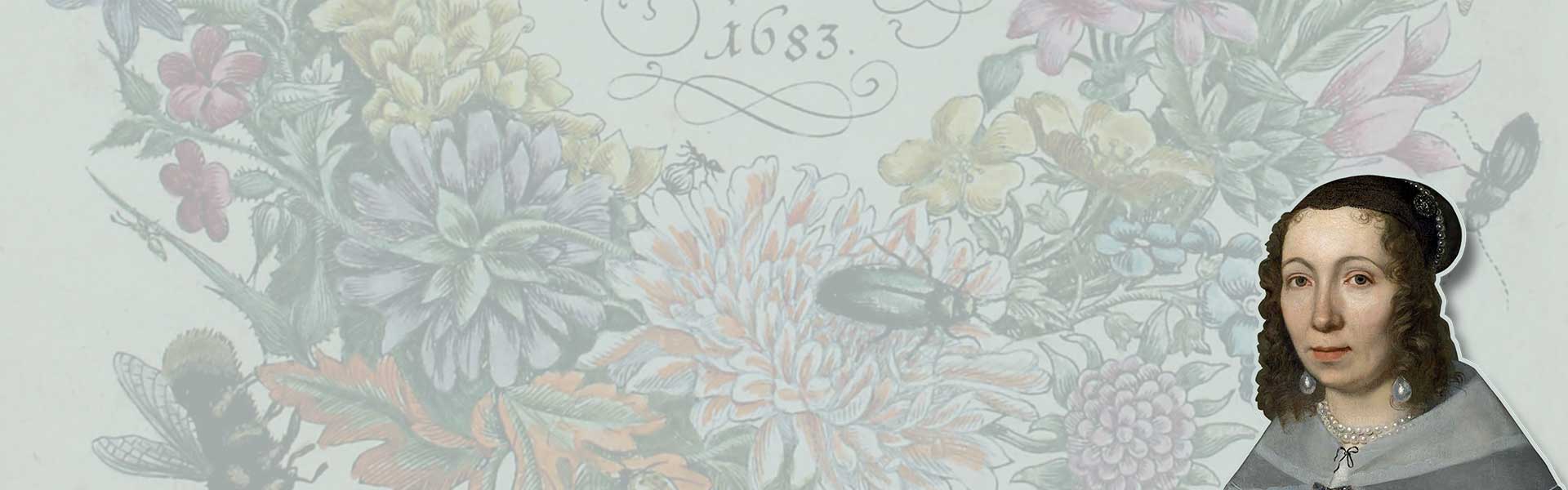

Just as in the case of libraries, educated and wealthy citizens of Nuremberg wanted to emulate these rulers and collected everything that was rare and interesting. These treasures, kept in a chest or – depending on the purse - in a separate room, the Cabinet of Curiosities (“Wunderkammer"), were willingly shown to visitors. They were, on the one hand, status symbols and, on the other, proof of local interest in everything related to nature in the time when Maria Sibylla Merian lived in Nuremberg.

The two treasure chambers on the ground floor of the Tucherschloss Museum (1) in the north-east of the old city centre of Nuremberg appear “tidier”, but with their diverse treasures on show they still remind us of the cabinets of curiosities of rich Nuremberg families in the Baroque era.

Tulip bulbs were popular collectors' items at that time, and Maria Sibylla's stepfather Jacob Marrell was not only an artist but also an experienced dealer in tulip bulbs. He was an excellent flower painter, too, so Maria Sibylla Merian was able to arrange a number of things in which Nuremberg collectors were very interested. Her ability permanently and admirably to capture the temporary, springtime splendour of a precious tulip in watercolours was particularly in demand, since at other times of the year, too, a Nuremberg merchant wanted to show his business associates visiting from Venice or Lübeck how the inconspicuous bulb in his collection could develop into a flowering miracle.

But not only beautiful things were collected. Rare and bizarre things were equally popular. In autumn, the Nuremberg physician, botanist and collector Johann Georg Volkamer the Younger (1661 - 1744), received a letter with an offer of various examples of this kind of "curiosity": 1 crocodile, 2 large snakes, 18 smaller snakes, 11 leguanas, 1 gecko and 1 small turtle for the all-inclusive price of 20 gulden. (2)

Since the letter came from Amsterdam, it is not difficult to guess the sender: the businesswoman Maria Sibylla Merian valued her customers, who perhaps even sold some items to a third party: "If the Honourable Sir is inclined to accept them, I will gladly tell him when I receive new animals; and if I can serve the honourable Sir in anything, he will be welcome to command".

The curiosity of Nuremberg's citizens and their passion for collecting and documenting as much as possible open up completely new perspectives on this city’s past. For example, a three-hundred-year-old etching (3) shows that a woman was also among the collectors, as she was obviously depicted with her favourite pieces: shells, medals and prepared butterflies.

Some of the treasures from her Cabinet of Curiosities arranged here are part of an etching depicting Esther Barbara Sandrartin (who is presented in the chapter on "Switched Identities" because the woman portrayed in the etching was often referred to as "Maria Sibylla Merian"). In the wooden box there are dissected butterflies, pinned cocoons and maybe even an empty cocoon of a butterfly which has already emerged (left).

A well-known travel writer was so impressed that he described her collection over several pages. He was pleased to note that she "took great pleasure in showing the rarities collected as her pastime to strangers". His praise shows that other remarkable women were also living in Nuremberg in Merian’s time: "Mrs Sandrart herself is one of the greatest rarities of her cabinet, if one considers her sprightliness in old age and incomparable memory at the age of 80. She knows the name of everything, the people from whom she got the items, the name of the herb or tree on which almost every kind of papilloas [butterflies] seek their food and reproduce”. Maria Sibylla Merian was thus able to converse expertly not only with men, but even with a woman during her Nuremberg years.