PAINTERS’ ACADEMY AND ORDER OF FLOWERS

During the years of economic boom after the end of the Thirty Years' War, Nuremberg attracted highly qualified specialists in the arts and crafts, who often settled there for good. They also helped to ensure the qualified training of the next generation. Thus in 1662 Jakob von Sandrart was able to establish the innovative painters’ academy. His famous uncle, Joachim von Sandrart, who had already been active there as a painter during the Peace Congress, stayed on in Nuremberg permanently. One of the directors of the painters’ academy was the “Flachmaler” (flat-panel painter), Johann Paul Auer, who taught Maria Sibylla and whose father, a wine merchant, had been the godfather and guardian of Johann Andreas.

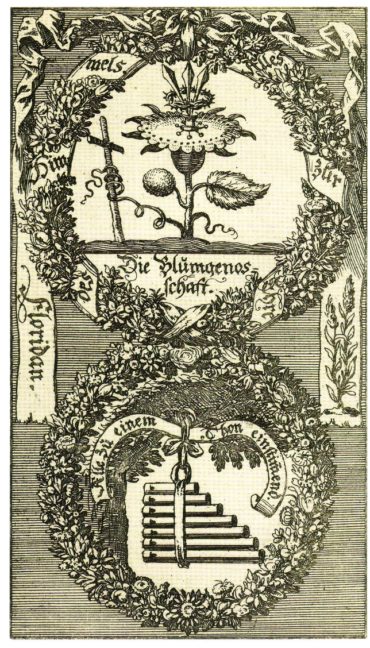

The term "art" must be understood in a very broad sense in Nuremberg. The "art of language" also belonged under this banner, as the example of the "Pegnitz Order of Flowers" shows. One of the earliest societies in the German-speaking world for the cultivation of the German language, it was founded in 1644 and still exists today. (1)

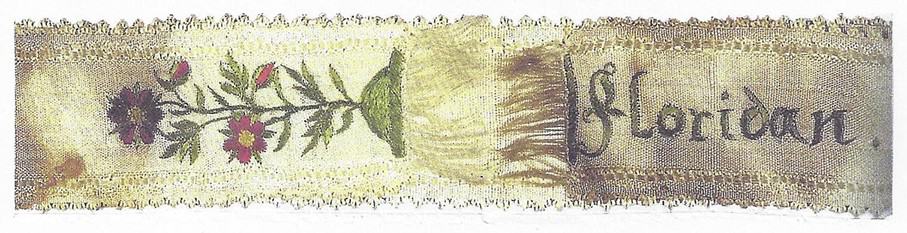

At that time, people deplored not only the loss of many lives and material goods. Violence, pillage and crime had also brutalised people’s manners and behaviour, and this was seen as a threat to urban culture. This is why educated people met in a “poets’ grove” on the banks of the River Pegnitz, west of Nuremberg, where they recited and shared their rhyming and non-rhyming texts in order to further a new linguistic culture. They wanted to avoid salutations involving the enumeration of lengthy titles, which normally would have been required due to class distinctions and so all members of the Order were given a fictitious name, usually that of a flower, together with a ribbon embroidered with that particular flower.

Ribbon of the Order belonging to this founder (2)

Even women were admitted to this association – almost as a matter of course (3) – and there were several corresponding members, who lived in other towns and cities, some of them far-away. Christoph Arnold, as number five, was one of the first members of this society; he was a teacher at the Egidien Grammar School, principal preacher at Our Lady’s Church and owner of a fabulous private library. He was one of Maria Sibylla Merian’s most important patrons and with his poems in the Caterpillar Books he supported the positive reception of her innovative works in Nuremberg civic society.

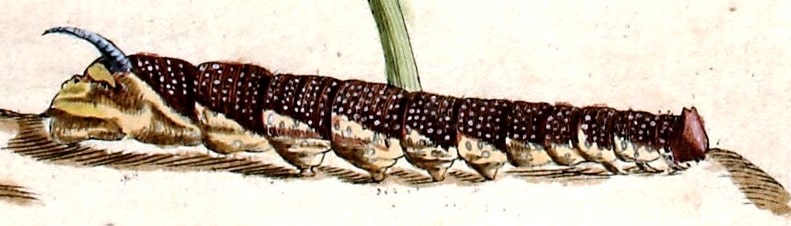

In her books Maria Sibylla combined her pictures with the results of her research and created a synthesis, a "Gesamtkunstwerk". In the prefaces she emphasizes several times that all her work is done to the glory of God. Professor Arnold endorses this additional religious aspect through his linguistic artistry in poems like the "Caterpillar Song" in the first Caterpillar Book, especially in the concluding seventh verse: (4)

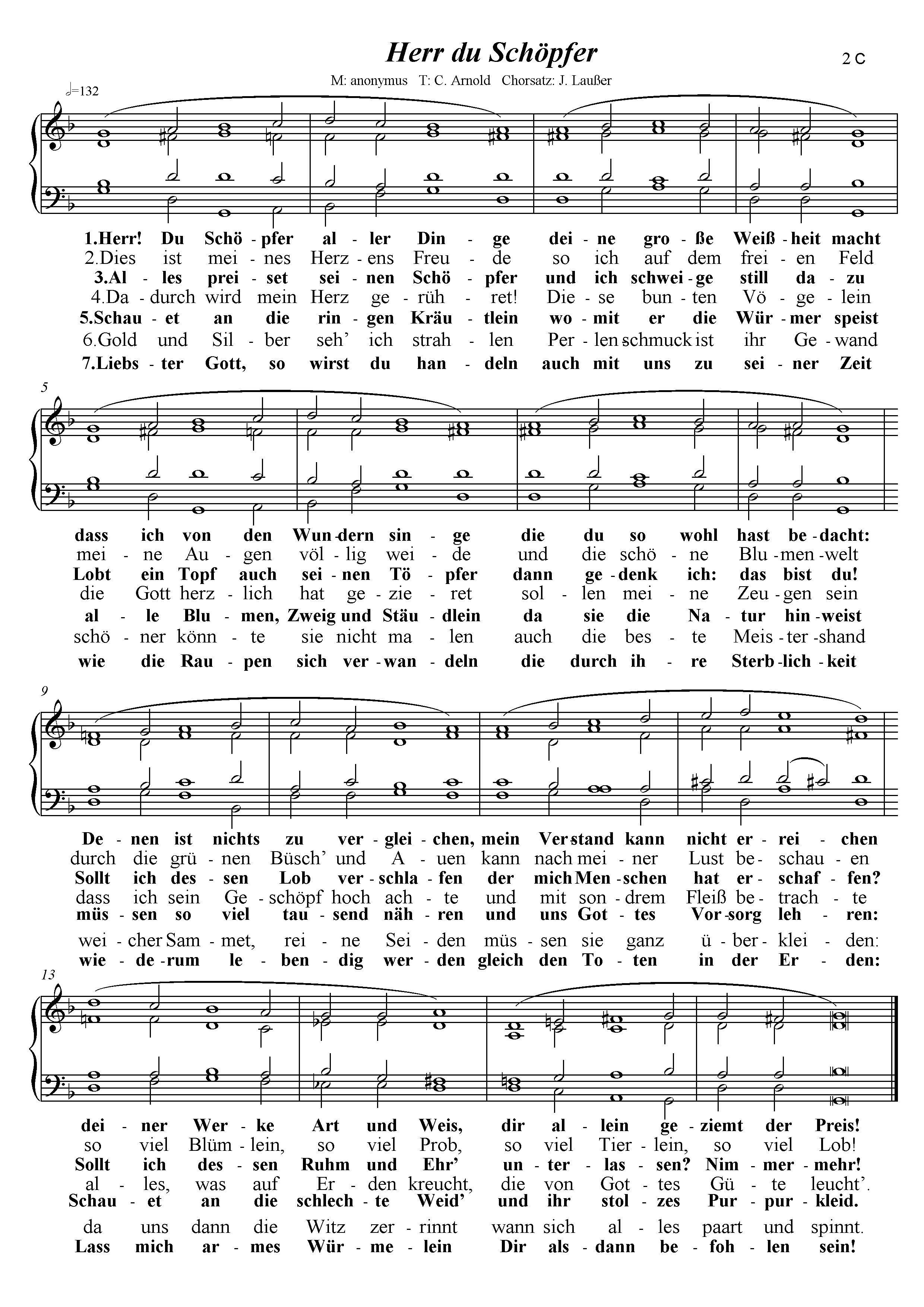

Arnold even brings music into play, because above the verses it says: "In the tune", that means, "In the melody of". We are sure that the ‘Caterpillar Song’ could indeed be sung, because we have found the melody of the hymn "Jesu, der du meine Seele" [Jesus, Who My Soul] with notes as number 718 in a "Nuremberg Songbook" from 1676, (5) i.e., from the time when Merian lived in Nuremberg. We even know what it sounds like today, since a choir of employees from the Nuremberg city administration have recorded it on CD.

At that time, art, research and faith were much more closely intertwined in Nuremberg city culture than they are today; and Merian's books are particularly vivid examples of this.

Raupenlied von Christoph Arnold abgedruckt im Ersten Raupenbuch von Maria Sibylla Merian