PARADISE FOR BUTTERFLY RESEARCHERS

Since the Middle Ages Nuremberg had been a city of gardens. With a growing population and denser building, many gardens were relocated outside the city walls in the protected area inside the outer defence ring right through to the fortified boundary ring with the redoubts. This is where not only the rich families who made up the city council, but also civil servants, medical doctors, lawyers, craftsmen and publicans created their own little paradise beyond the city, which in summer was stuffy and foul-smelling.

Johannis Gardens between St. John’s Cemetery (top left) and Hallertürlein (bottom right)

In the lower centre above the river: Hallerwiese, Nuremberg’s first public park from 1432 onwards

The ingenious draughtsman Hans Bien created a special image depicting the green belt of gardens during the Thirty Years' War, of which only the section between the small pedestrian gate called the Hallertürlein and St. John’s Cemetery is shown here. Within the city wall Bien has depicted only important buildings such as churches in detail, while outside the city wall the individual gardens can be seen in the minutest detail: the summer houses along the street; the side buildings in an L or U shape; the terrace behind the house with the balustrade and the lower part of the garden, which was often used for agriculture and where fruit and vegetables were harvested. The southern slope of the gardens captured the heat of the sun and favoured the growth of the precious citrus trees, which had to be protected in winter in a heated outbuilding.

During the Thirty Years’ War many gardens were damaged and summer houses even had to be demolished in order to safeguard a clear field of fire for the canons fired in defence of the city. But they were mostly half-timbered houses, whose beams were carefully preserved. By the time Sibylla Maria Merian came to Nuremberg in 1668, the houses had long been rebuilt and gardening had once again become the dominant passion of Nuremberg people from the upper and middle classes.

The western summer gardens shown in the above illustration are only a small part of the many gardens that encircled the city like a necklace. At the end of the 17th century there were about 380 gardens in the protected area between the ring of the city walls and the Landwehr. (1) They were complemented by the large, noble gardens in the Old Town, e.g. in the east on the Schwabenberg and behind the Tucherschloss as well as on the Zwinger of the city wall - a total of more than 400 gardens.

Maria Sibylla was permitted to observe fauna and flora in quite a few of them. In several places in the Caterpillar Books as well as in her Book of Notes and Studies (Studienbuch) we find notes on where she collected her finds. In the course of her research in the large territory outside the Imperial City, she found interesting caterpillars in the “Irrhain” (labyrinth grove), the little park of the “Pegnesischer Blumenorden” (a literary society founded in 1644) near ,the village of Kraftshof north of Nuremberg, and in the city moat of Altdorf, a day’s journey to the east. (2) News about her research interests spread fast, her female disciples (3) helped her and a rare caterpillar was even sent to her from Regensburg. (4)

In Nuremberg, not only were the many private gardens a special attraction, but there had even been a public park since the Middle Ages, after the Council had acquired, in 1432, a sizable strip of river bank directly west of the city wall from one of the oldest and most distinguished Nuremberg families (the Haller). This "Hallerwiese", named after the previous owners, can be easily recognized in the above drawing by Bien by the regularly planted trees along the riverbank. The details become even clearer on the detail from a 360-degree view of the city from around 1580 (5) which depicts tree-lined alleys, two fountains and many leisure activities: a small boat on the river, walkers with a dog and a sunbather. Little has changed since then. Today, after almost 600 years, the Hallerwiese is still a very popular public park close to the city centre.

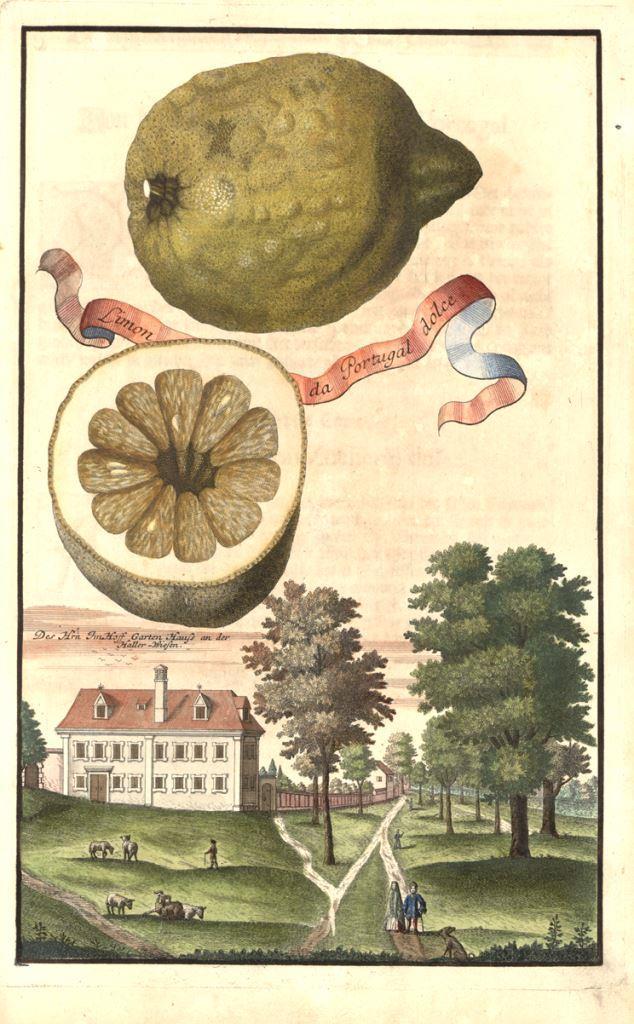

The green ring around the historic city was almost completely destroyed in the 19th century through industrialisation and the growing population. But its memory is preserved, because the merchant Johann Christoph Volkamer (1644-1720) wrote a comprehensive book about the gardens in Nuremberg and their culture, which he published in 1708. Volkamer was the brother of Merian's longtime correspondent, he was only three years older than her and they knew and esteemed each other.

Volkamer's book is one of the most important and peculiar publications about the gardens of that age. At first glance, the views of gardens, landscapes and other sights (veduta) on the engravings appear to be of secondary importance. Their cultural and historical significance only becomes apparent on closer inspection, for most of the space is taken up by the many varieties of citrus fruit known in Nuremberg, in their original size, without leaves if they were sent in by other collectors, with green foliage if they grew and were harvested there. (6)

Since Nurembergers in the Baroque period also liked to show off their knowledge of the ancient world of the gods, Johann Christoph Volkamer (the brother of Maria Sibylla's correspondent) named his book the "Nuremberg Hesperides", referring to an ancient legend: these nymphs were commissioned to guard the tree with the golden apples (oranges?) belonging to the mother goddess Hera. This work is a lasting testimony to the Nurembergers' love of nature, their curiosity about the unknown, such as exotic plants, their willingness to invest not only money but also a lot of time in this hobby and to share their experiences with one other.

Like Maria Sibylla Merian, Volkamer combines two themes in his work: a comprehensive botanical representation and description of the exotic citrus fruits; and the buildings and garden layout necessary to provide the basic conditions for the cultivation of these plants, namely, gardens and garden houses to accommodate these guests from far-away countries.

This book contained so much advice on the cultivation and care of plants and even on the combating of parasites that it was considered a standard work of garden culture in the 18th century. Volkamer also wrote a separate chapter on gardeners as a class, which for him was "blessed before others". At the end of the chapter he placed an engraving of a gardener and his assistant at work.

On the solid, stone balustrade stand the expensive, exotic trees that the gardener waters while his assistant works on an ornamental bed. Both are framed by a variety of tools which bring everything together to create a true-to-life, miniature work of art.

Volkamer's book has certainly also contributed to the fact that since the 1980s, at the request of the citizens of Nuremberg, three Hesperides Gardens have been reconstructed according to old plans in the Johannis quarter. For this, the city of Nuremberg was awarded a Europa Nostra Medal in 1988. The flourishing horticultural heritage from the time when Maria Sibylla Merian lived in Nuremberg can thus remain alive.