PROSPEROUS TIME FOR THE CITIZENS OF NUREMBERG

The Thirty Years’ War marked a decisive turning point in the city’s development. While the city was never conquered, the price were major financial contributions to the war. Many lives were lost due to epidemics; and the economy and cultural life suffered badly. Nevertheless, the city recovered quickly after the Treaty of Westphalia (1648). For a year after the war, the Congress for the Implementation of Peace sat in Nuremberg, negotiating the demobilisation of troops, the payment of compensation, and other important details. Diplomats and their delegations lodged in the city; they needed food and new, elegant clothes; they had their portraits painted in oil or etched in copper; they celebrated many festivities. All this was an effective economic and cultural stimulus package (more comprehensive than a Marshall Plan).

When the young couple, the Graffs, came to Nuremberg in 1668 with a still very small infant, a refreshing wind blew through this city. Maybe Nuremberg urban society made settling down relatively easy, with newcomers able to find a foothold here in the first generation, in this centre of draftsmen, painters, copperplate etchers, printers and illuminators. This positive development continued into the last decades of the 17th century, even though some qualified immigrants had to overcome initial difficulties. The printers of the First and Second Caterpillar Book (1679 and 1682), Andreas Knortz from Kulmbach and Michael Spörlin from Frankfurt, are interesting examples of the opportunities and risks for such "new citizens" (cf. chapter on Maria Sibylla Merian's Nuremberg Works).

In Lutheran Nuremberg it was not unusual for women to work as painters, embroiderers or teachers of girls. Idleness was considered a vice and even girls in the upper strata of society had to learn something useful. Maria Sibylla’s “Jungfern Combannÿ” (Company of Maidens) included daughters from the elite families which served on the City Council, such as Clara Regina Imhoff, as well as from the middle classes which worked in trade and the arts and crafts, such as a daughter of the art dealer and publisher Paul Fürst.

Many Nuremberg citizens were curious about everything connected to nature and plants and they were prepared to spend money on this interest, including the buzzing and fluttering creatures living on the plants. Therefore Merian’s interest in caterpillars was not considered “sinful” and caterpillars were by no means despised as “Teufelsgewürm” [the Devil’s worms]. Prepared butterflies were an attractive part of private collections in cabinets of curiosities (“Wunderkammern”).

Science and reverence for God’s wonderful creation, including the smallest and most insignificant creatures, corresponded closely to the attitude to life in Nuremberg civic society. Thus in Nuremberg Maria Sibylla did not have to fear being prosecuted for her research into insects. On the contrary, her work was supported.

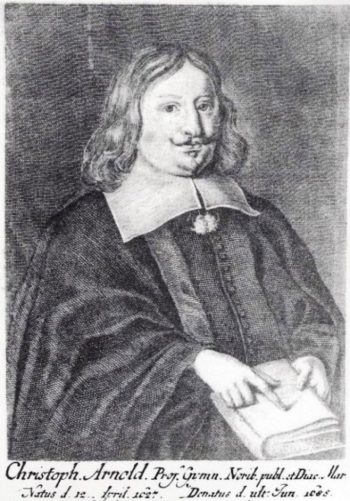

Particularly eloquent examples of the recognition and admiration of Nuremberg civic society are the poems by her mentor Professor Christoph Arnold in both Caterpillar Books. In her First Caterpillar Book we find such a poem directly after the title etching and printed title page. There Arnold places the female author on a par with the most famous insect researchers of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries who had published their findings before Maria Sibylla.

Portrait of Christoph Arnold (1)

“It is cause for astonishment / that women, too,

trust themselves to write / judiciously /

on what has occupied the hordes of scholars so much.”

With this central statement he virtually gives Merian's work the seal of approval, contributing significantly to her recognition in Nuremberg:

“But it is laudable / that a woman strives to emulate

their [the men’s] deeds. […]

that an ingenious woman / achieved all this / to while away her time.”

At the beginning of the 1680s Maria Sibylla had developed into a specialist in flowers and caterpillars and her husband had become a pioneer of city scenes. Both had good prospects for a successful, secure future. For the Graff-Merian family, however, the Nuremberg period came to an unexpectedly rapid end after the death of the head of the family, Jacob Marrell, in Frankfurt in November 1681. His aged widow, Maria Sibylla Merian's mother, was not provided for and needed help, so Maria Sibylla returned to Frankfurt with her husband and daughters in 1682.

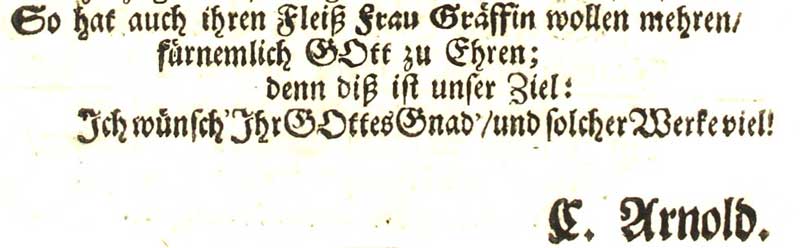

The continuing benevolence towards Merian as a "temporary Nuremberger" is also expressed by Arnold in the Second Caterpillar Book in a poem that sounds like a farewell. (2)