LIBRARIES AS KNOWLEDGE Stores

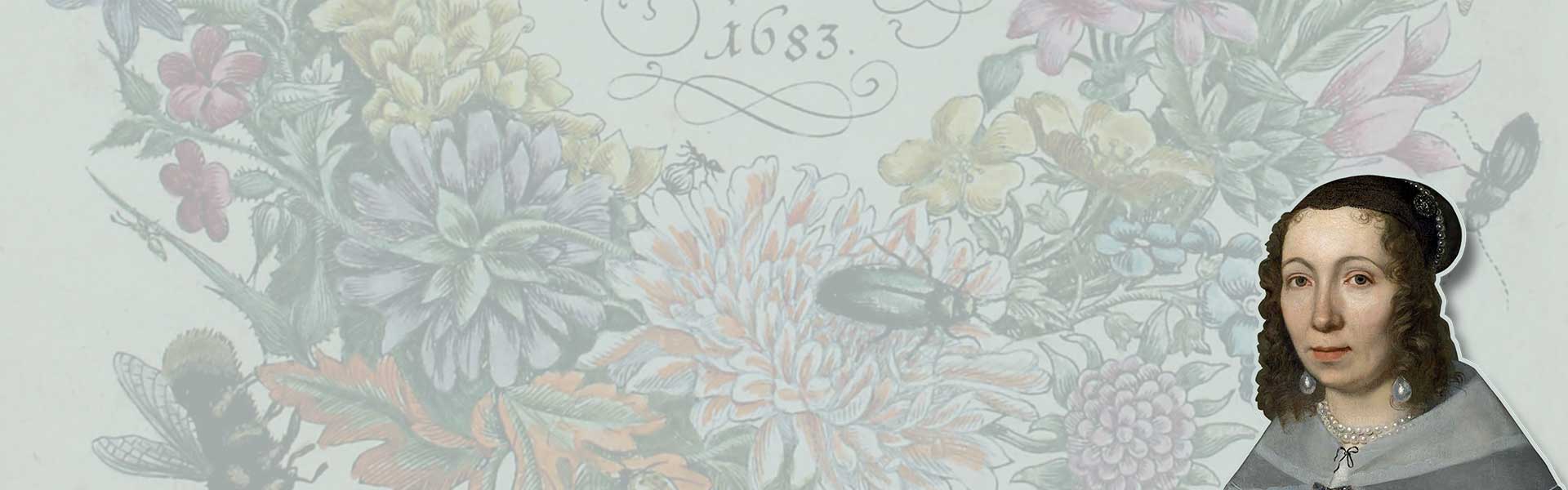

Knowledge and success have always been closely linked in Nuremberg as a city of merchants and craftsmen. They travelled a great deal for their jobs and brought home new knowledge about the latest inventions and political developments. They wrote numerous letters, and it is remarkable that such material is still kept in libraries, archives and museums today, even though the letters may at first seem quite unimpressive and perhaps even unimportant. It is, therefore, especially worthwhile to search for facts about Sibylla Maria Merian's life and work in Nuremberg and in the university library of the neighbouring city Erlangen. For example, the majority of Merian's letters known to date have survived the centuries there.

Collecting books as a "store of knowledge" had been popular in Nuremberg since the Middle Ages, when everything had to be written by hand. Nuremberg City Library celebrates its 650th anniversary in 2020. After the monasteries were dissolved in the 16th century this growing library was housed for centuries in the spacious buildings of the Dominican Monastery directly to the north of the City Hall. No official deed has been discovered testifying to the foundation of this library, but a small document from 1370 bearing a seal records the loan of an item. This receipt for a library loan (“Lehschein”) in German, not in Latin (!), proves that the council library already existed at that time.

From various historical sources we can reconstruct the fact that that many Nuremberg citizens in the 17th century were keen book collectors. They were proud of the collections in their private libraries and lent each other books, which included not only theological and legal works. In the Natural Sciences, specialist books on medicine and geography, but also on botany, were in great demand. A total of seventy private libraries are recorded in the late 17th century, when Sibylla Maria Merian lived in Nuremberg.

One of the most enthusiastic book collectors in the 17th century was Professor Christoph Arnold, who - apart from her own husband - was Sibylla Maria’s most important advisor and patron. He was a teacher at the Egidien Grammar School, Dean at the Church of Our Lady and one of the first members of the “Pegnesischer Blumenorden” [Pegnitz Order of the Flowers], the famous literary society for the promotion and improvement of the German language which still exists to this day.

Arnold not only knew the names of these authors, but kept several of these Latin, English, Dutch, Italian and Spanish works in his private library. His collection comprised about 9,500 printed works; and this was only one of the many private libraries in Nuremberg at that time. Doubtlessly, Maria Sibylla was familiar with such bibliographical treasures and took a close look at the pages with illustrations of insects and spiders.

However, the people of Nuremberg were not only avid collectors but also diligent producers of books. For example, as early as 1613 the Nuremberg pharmacist, botanist, collector and engraver Basilius Besler (1561 – 1629), under commission from the Bishop of Eichstätt, had published the magnificent book “Hortus Eystettensis”. The work shows plant species from all over the world. It was a large-format botanical work with a first edition of 300 copies - a gigantic project for its time. It was so voluminous that one part was printed in Nuremberg and another part in Augsburg. On 366 pages (one for every day of the year), over 1,000 plants from all over the world were depicted on copperplate etchings and reflected the course of the year. (4)

The Prince Bishop of Eichstätt spared no expense with this work. He wanted to show, at any time of the year and without a visit to the actual location, what treasures his garden below the Willibaldsburg Castle had to offer. Fifty years later the book was still being diligently hand-coloured (= illuminated) in Nuremberg. A beautiful, coloured copy cost as much as a small house in Nuremberg.

Copper etchings from the Hortus Eystettensis, Augsburg and Nuremberg, 1613 (5)

Perhaps Maria Sibylla was already able to see a hand-coloured copy in Frankfurt, but she certainly could in Nuremberg. There she might have looked over the shoulder of her pupil Magdalena Fürst as she carefully coloured (= illuminated) a copy in years of work until 1677.

In a city where scientific publications were produced and successful, Maria Sibylla could count on a great deal of interest in her own books. The various title pages address the respective clientele.

- The Flower Books were intended for "young people eager to learn, women and art lovers, i.e., for amateurs".

- The Caterpillar Books, on the other hand, were aimed at experts and knowledgeable garden owners: "naturalists, painters and garden lovers".

These books were all printed in Nuremberg . For the Caterpillar Books we even find the names of the printers on the title pages: Andreas Knortz and Joh. Michael Spörlin (cf. chapter Nuremberg Works/138 copperplate etchings).

Her masterpiece on Surinam Insects (1705) also received attention in Nuremberg and was already mentioned three years later in the great work "Nuremberg Hesperides" by Johann Christoph Volkamer, which is known as the standard work for gardening with citrus plants in 18th century. Throughout the following centuries and until today – at least in Nuremberg – Merian's works have never fallen into oblivion.