WHAT THEY HAD IN COMMON – WHAT SEPARATED THEM

Outline – Second Part

2. Success, Crisis and Separate Ways

2.1 The “Gräffin’s” Last Years in Nuremberg until 1682

2.2 A Long Family Visit by Jacob Marrell

2.3 Graff’s First Master Etchings

2.4 Return to Frankfurt

2.5 Graff’s Commuter Years until 1685

2.6 Months of Change 1685 / 1686

2.7 Breakdown of the Marriage in the Labadist Colony in Friesland in 1686

2.8 Continued Links with Nuremberg

2.9 Merian’s and Graff’s Two Daughters – Artists Finding Their Own Way far afield

Abbrevations of Archives etc.

Abbreviations of Various Fields of Literature

Endnotes

Additions to the Literature References in the First Part of this Essay

Women on the Margins

(Lit 1995), p. 141

But she is a harder person to pin down …, since she left behind no autobiography, confessional letters, or artist’s self-portrait. Instead we must make use of the observing ”I” in her entomological texts and fill in the picture by attending to the people and places around her.

Drei Frauenleben

Translation by Wolfgang Kaiser (Lit. 1996), p. 170

Aber sie läßt sich schwieriger fassen …, denn sie hat keine Autobiographie, keine Briefe mit persönlichen Bekenntnissen, kein Selbstbildnis als Künstlerin hinterlassen. Statt dessen müssen wir uns auf das beobachtende „Ich“ in ihren entomologischen Texten stützen und uns mit Hilfe der Menschen in ihrer Umgebung und der Orte, an denen sie sich aufhielt, eine Vorstellung von ihr machen.

2. SUCCESS, CRISIS AND SEPARATE WAYS

2.1 THE “GRÄFFIN’S” LAST YEARS IN NUREMBERG UNTIL 1682

Towards the late 1670s, Maria Sibylla, as a wife with an acknowledged “regulated, well maintained household” (Joachim von Sandrart) (1) had to cope with an enormous burden of work. She was a mother, business woman, draftswoman, painter, embroiderer, copperplate etcher, teacher, observer of nature, collector, taxidermist, pigment specialist, and author of non-fiction books, all at the same time. Without continuous support from those around her, she would never have managed to complete three printed works within only four years: in 1677, the second part of the Flower Book, in 1679, the first Caterpillar Book, and in 1680, the third part of the Flower Book published together with the first two parts as the complete edition of the “New Flower Book”).

Her husband must have been her most important helper, contributing more than the guarantee of indispensable legal and financial backing for his wife’s publications. As her publisher named in the title copperplate etching or on the title page (2) (“to be found with Graff in Nuremberg …”) his tasks included:

- buying copperplates and paper,

- negotiating with printers about the texts and paying them for their work,

- organising the sales of the (unbound) books etc.

Maria Sibylla could learn a lot from her partner who was 11 years her senior, benefiting from his skill in highly detailed observation and his long experience as an artist, etcher and copperplate engraver. She could surely also rely on him when she needed active support for the heavy work at the printing press which was probably housed in the ground floor workshop in the house “To the Golden Sun”. He must not only have tolerated the many boxes on the window sills for breeding the caterpillars and the resulting domestic disorder, but most probably will also have repeatedly instructed his older daughter as well as the pupils of the “Company of Maidens” to replenish supplies of fresh leaves of specific food plants, and to observe the metamorphoses, so that Maria Sibylla could fixate the “little summer birds” – butterflies (“Tagfalter”) and moths (“Nachtfalter”) immediately after they first spread their wings to prepare them for her studies.

The formal design of the first Caterpillar Book surprises with a clear layout with a title copperplate, a title page, a laudatory poem, a 4-page foreword to the “Esteemed Art-Loving Reader”, followed by 50 copperplate engravings with matching detailed descriptions on separate pages, as well as a second poem (the “Caterpillar Song”), a 4-page register (in German), an additional index (in Latin), and, on the last page, even notes for the bookbinder and corrections of very few errata. There is a leap in quality compared with the previous issues of the Flower Books, which would have been unthinkable without expert assistance. As an experienced editor, Professor Christoph Arnold obviously not only enhanced the Caterpillar Books with his poems, but also contributed his expertise to their design.

In spite of this wide-ranging and varied assistance, Maria Sibylla seems to have often been on the brink of a nervous breakdown. In retrospect, Johann Andreas Graff, even in 1690, in a letter to a Frankfurt lawyer, gives a vivid description of those crises:

“Did she not in desperate situations (“Todesnöten”), plagued by satanic doubts … say unto me: that she would that all her works would be burnt in the world, and that her name would be erased from the face of the earth, but when I then comforted her with the Holy Name of Jesus, behold, then she was of a healthy mind again the next day! And I found her spinning and thanked God for that!” (3)

During this busy time, Maria Sibylla became pregnant again, and in early February 1678, ten years after the birth of her first daughter, a little sister Dorothea Maria was born in Nuremberg. (4) She was probably christened in St Sebaldus’ Church over the same font as Albrecht Dürer, unless the parents preferred a home christening. This was quite possible in Nuremberg. Some Reformed-Pietistic families chose this option – and both Matthäus Merian the Elder who had come from Basle to Frankfurt and Maria Sibylla’s mother from Runkel (on the river Lahn near Frankfurt) (5) adhered to this faith.

The godmother was the painter, Dorothea Maria Auer (1641-1707), daughter of the wine merchant, Johann Andreas’ godfather. (6) She remained unmarried all her life, like quite a number of other women who were active in the arts. By this time, single marital status was no longer considered a stigma in Nuremberg. The Auers had an excellent family network in Nuremberg – a good reason for the Graff-Merian family to choose the “Jungfer Auerin” (damsel Auer) as godmother and name their second daughter after her. An older brother, Johann Paul Auer (1638-1687), was a well-known painter and was one of the heads of the painting academy and also taught Maria Sibylla.

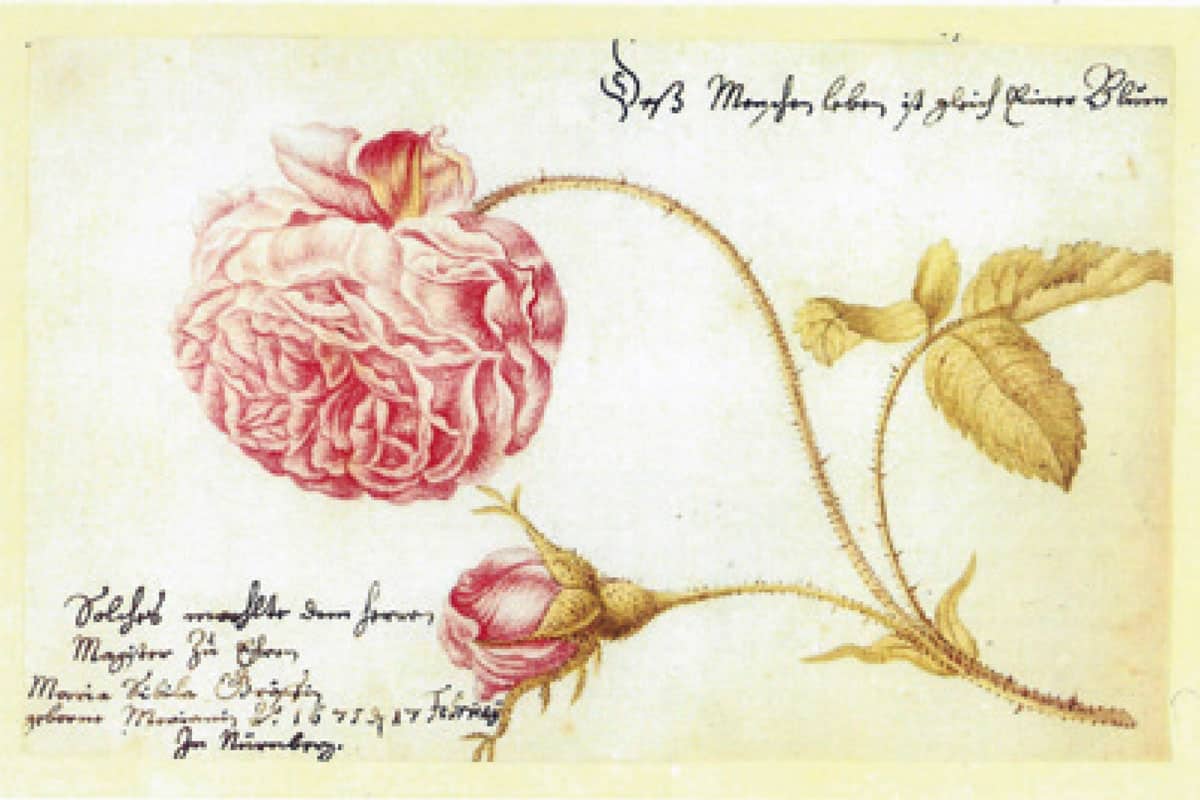

Maria Sibylla hardly talked about her own life, but on two album pages, she used a watercolour motif of the hundred-petalled rose which is often interpreted as a depiction of various stages of life, starting with the bud right through to the wilting flower.

Album Page with Rose (7)

To the first album page of 1675 for “the learned professor” (without adding his name), presumably the scholar Christoph Arnold, she added the pensive saying on the top right: “Man’s life is like a flower”.

On the second album page (1679), there is no such saying which might suggest that the pious mentor was a kindred spirit. This page is just signed and dated. The second rose seems more tired, bud and stem touch the ground which is suggested by a shadow. Maybe, in spring 1679, Maria Sibylla felt a similar fatigue. Nevertheless she continued to work unabated. Indeed, there was major demand, not only for the Flower Books, but also for the first Caterpillar Book, as demonstrated by the many copies extant in the Nuremberg area alone, often carefully illuminated. After the publication of the first Caterpillar Book, she therefore started busily collecting, etching, and writing descriptions for the second Caterpillar Book. More and more, she develops into an independent personality, and in the foreword to the second Caterpillar Book no longer thanks anyone for “assistance well-provided”. Her growing self-confidence is also demonstrated by the greater prominence of her signature.

In 1679, her name is almost hidden between the branches of the mulberry tree, but by 1683, the line “Maria Sibylla Gräffin sculpsit” stands out under a sumptuous wreath of flowers with many insect visitors.

Excerpt from the Title Page of the First Caterpillar Book

Excerpt from the Title Page of the Second Caterpillar Book

2.2 A Long Family Visit by Jacob Marrell

From autumn 1678, the head of the family, Jacob Marrell, who had taught both Maria Sibylla and Johann Andreas and was an important father figure to both, resided with the Graffs for an extended period. On 5 November, 1678, Nuremberg Council approved a special application: Jacob Marrell was permitted “to reside with his step son-in-law, Johann Andreas Grafen resident here ….” (8) This residence permit as a “protected relative” (Schutzverwandter) will certainly have been liable to charges, and the application made by his son-in-law implies that the guest was intending to stay for a long period of time.

The proof of Marrell’s presence in Nuremberg in 1679 is a drawing in the Album amicorum of Andreas Arnold. Date and signature at the bottom right are unambiguous: "In Nuremberg, this 3 June. A° 1679 Jacob Marrell". The dog roses, together with the hundred-petalled rose drawn by Maria Sibylla and the realistic and at the same time atmospheric view of the shores of the River Tiber, with a Roman temple, by Graff, constitute particularly pretty eye-catchers in the same Album amicorum.

Christoph Arnold, the father of the owner of this little book is respectfully honoured as “Honourable and Most Learned Professor”, although he is not named. His flower in the Pegnesian Order was the dog rose.

But the humorous verse at the bottom right also shows a connection as an equal with the son, Andreas Arnold, maybe even providing a motto for the beginning of his grand tour of European cities?

“Common is rose picking (= normal),

But beware of thorns a-pricking.”

Album Page with Dog Rose (9)

So Marrell was not only active as an art merchant in Nuremberg and took part in family life with his two (step) granddaughters in the house “To the Golden Sun” for some time, he also painted in Nuremberg.

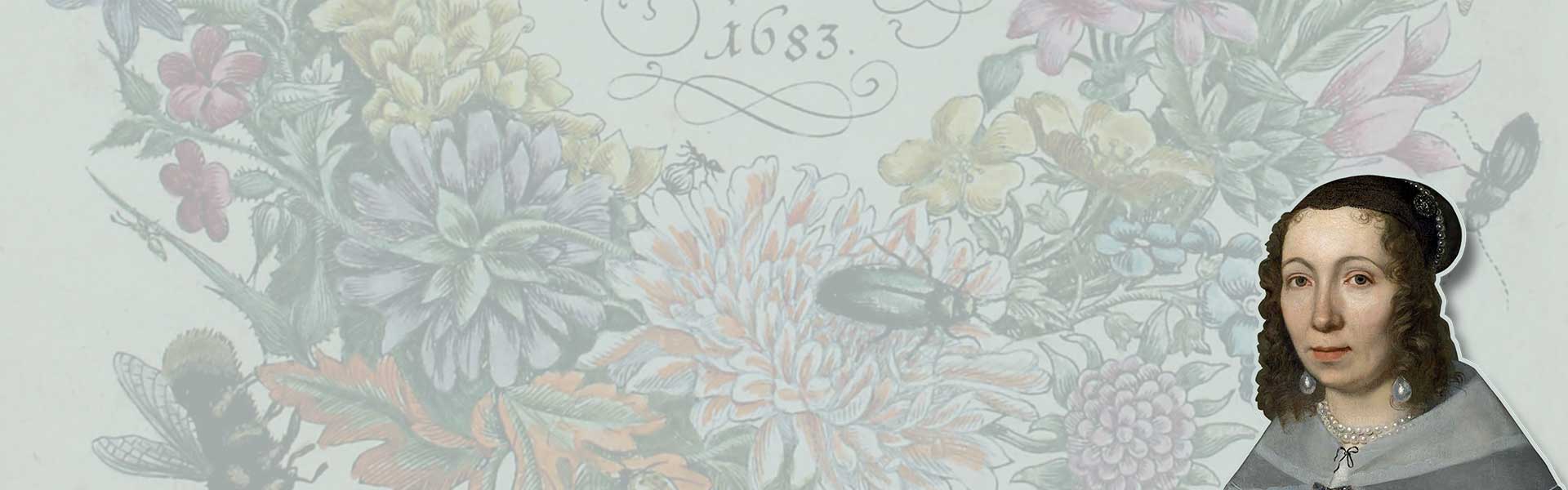

There is a portrait in the Kunstmuseum Basel which at the back carries the inscription: „MARIA SIBYLA MERIAN AET · SVAE 32. ANNO 1679.“ At that time Maria Sibylla was indeed 32 years old and was probably breast-feeding her little daughter.

By comparing the style, experts think it is plausible that this painting was created by Marrell. (10) The serious, alert eyes of the no longer very young woman looking at the viewer would definitely be right for her. The subdued colour of clothing was worn in Nuremberg as well as in the Reformed Netherlands, in particular by women from immigrant religious refugee families. Other portraits show that the combination with precious pearl jewellery was not considered unsuitable.

Portrait of “Maria Sibyla [sic!] Merian” (11)